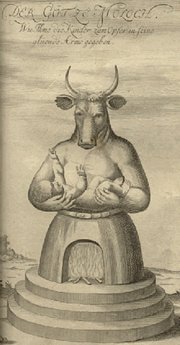

Molech

From Plastic Tub

| Revision as of 01:41, 3 Aug 2005 Payne (Talk | contribs) ← Go to previous diff |

Revision as of 01:31, 19 Aug 2005 Undule (Talk | contribs) Go to next diff → |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

| <tr> | <tr> | ||

| <td width="*" align="left" valign="top">__NOTOC__ | <td width="*" align="left" valign="top">__NOTOC__ | ||

| - | '''Molech''' (מלך-''Heb.'') ''pn.'' '''1.''' An ancient [[God]] to whom worshippers sacrificed valuable posessions, often in the form of human life. '''2.''' A magician, illusionist or trickster. '''3.''' ''euph.'' A scientist or a worker of technological marvels. | + | '''Molech''' (מלך-''Heb.'') ''pn.'' '''1.''' An ancient [[God]] to whom worshippers sacrificed valuable posessions, often in the form of human life. '''2.''' A magician, illusionist or trickster. '''3.''' ''euph.'' A scientist or a worker of technological marvels. '''4.''' A murderer of children; an abortionist. |

| == Extrapolation == | == Extrapolation == | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

| ---- | ---- | ||

| - | <font style="font-size: 92%"> | + | <font style="font-size: 90%"> |

| In the twentieth century, Molech has served as a popular metaphor in the arts. He features prominently in Allen Ginsberg's ''Howl'' and in Fritz Lang's ''Metropolis''. | In the twentieth century, Molech has served as a popular metaphor in the arts. He features prominently in Allen Ginsberg's ''Howl'' and in Fritz Lang's ''Metropolis''. | ||

Revision as of 01:31, 19 Aug 2005

|

Molech (מלך-Heb.) pn. 1. An ancient God to whom worshippers sacrificed valuable posessions, often in the form of human life. 2. A magician, illusionist or trickster. 3. euph. A scientist or a worker of technological marvels. 4. A murderer of children; an abortionist. ExtrapolationThe Filament of History In speaking of Molech 1 one must be aware, set asmoke cencers of protection, elaborate chalk drawings on the basement floor, play rock tapes in reverse, roll up one's sleeves and divvy the distinctions between the general phenomena of Molechianism, as particularly known to those prone to such things, flipping enormous hair-dos, and the particular name itself, Molech, as it refers to the popularly understood and oft-exclaimed Semitic manifestation, Yahweh. His Balls Flopped Out In Biblical 2 Canaan, Molech (or Chemosh, Melqart, or Ba’al) was worshipped as the Lord of Fire and God of War. The name itself is generally understood to mean “King” or, more generally, “owner.” Though most closely associated with Hebraic tradition, Molech cults thrive wherever populations outgrow natural resources or suffer extraordinarily enduring hardship: in a classically Malthusian sense, the God functions as a regulator of society, limiting excess population and controlling access to food, water and arable land. Thus, Molechianism naturally occurs in desert regions such as the Middle East and North Africa as well as in other areas affected by anomalous terms of drought, plague and social upheaval. Ritual Formations Though Molech could be sated through the spilling of both animal and human blood, the hungry God seemed to prefer infants – particularly those who were seen as valuable, such as a cowled child or the son of a chieftain. Sacrifice must hurt or it has no meaning to the community; the offering of a crippled beast or vegetables could summon supernatural ire, resulting in loss in battle, boils, clouds of locust and all manner of ill-fated incidents. This concept is illustrated ably by the Old Testament story of Cain and Abel – Cain being cursed for offering fruits and vegetables, light fare compared to his brother's sanguine animal sacrifice. This metaphysical system acts in a manner familiar to many speculators in the Capitalist Stock Market – great risk, or sacrifice, yields greater returns. But there is also the slow steady approach of the tortoise, a gradual amassment of comparatively smaller yields, the substitution of quantity for quality. This could explain the mass execution of innocent persons to be witnessed in the Old Testament, The Vedas and countless other sacred texts: the slaughter of hundreds or even thousands can substitute or surpass the offering of single prized child. Thus, the act of war itself, particularly those waged as acts of “ethnic cleansing”, can be seen indeed as a form of worship, expiating the hungry god whose favors are bestowed from a river of innocent blood. Indeed, some researchers conflate any taking of life with Molechian sacrifice – the execution of prisoners or abortion for instance. Believers in this view usually display pronounced Gnostic tendencies, such as those exemplified by The League of Gnomes and associated subgroupings. This line of thinking arises from the Gnostic belief in the evil of material existence which is associated with a False God, the entity responsible for suffering on this plane and whose efforts are directed at subverting the divine spark in man. This presents no subtle metaphysical quandary: the taking of a life removes it from the grips of the False God, sending the spirit hurtling beyond the material realm and into renewed combat in the Pleroma. This view is curious, however, in that Molech is clearly identified as the creator of the World, indeed, of flesh – he is the False God for whom the blood sacrifice is meant to foil. As in certain Gnomic rituals, the child’s flesh is eaten by worshippers – though it’s important to note that child needn’t be killed; often, a single limb would be adequate repast and more rarely, fingers, toes or even ears, lips and noses. Surviving children so honored became the communal ward of the Tribe; they were thought to have a keen sense of the God’s will and could be consulted for augurs and prophecy. Thanatologically Speaking In the end, nearly all human religious practice is Molechian in its eschatological preoccupation with death – all human worship exists to explain (or cheat) death, to assuage the worries of the living and to imbue the act of dying with metaphysical portent. The true Molechian, however, very nearly worships the act of dying – and, more darkly, the act of killing. Life is defined by its cessation; its value autotelized by its limit. This metaphysical trade in death has powers of influence over the world of the living – if the God can be made drunk with innocent blood, his will becomes the malleable subject of human influence, clay in the hands of the potter. The only issue to be decided then, is over what sphere Molech/Yahweh/Mormo 3 reigns? Is he the creator of all things or simply a spiritual monstrosity, blind to his superiors, lost among the Pleroma as even man himself is lost inside his own flesh? Non-Canonical TextMolech enjoys notable ubiquity in the gnarled tradition of medieval Christian demonology; in fact, he appears as a kind of Superstar Prince of Hell, embroidered with an astonishing variety of descriptive illumination. His province was believed, as expected, to be the realms of fire, war and, curiously, dreams. In this latter capacity, Molech was alternately known as Mommu, a slight perversion of the Sumeria Mamu, the Lord of Dreams. See AlsoNotesNote 1: "Molech is a horrible beast, a soul-eater and a right bastard." So began Stimso Adid's exhaustive psychoanalytic study of Molech, The Oral God. Note 2: Explicit references to Molech appear in Lev. 18:21, 20:2-5; Jer. 32:35 and II Kings 23:10. Note 3: Jewish history can be read as an identity struggle - an attempt to wrestle a unique Yahweh asunder from Molech. Abraham struck the first blow, attempting to rip Yahweh from Molech by claiming that Yahweh ordered him to spare the life of Ishmael, Abraham's first born who was called to the sacrificial altar. Likewise, Solomon, in his vain glory, attempted to cleave the One when he built separate temples for Yahweh and Molech. But the gods are not so easily herded by men: Solomon's temple was soon reduced to rubble, and Yahweh eventually presented his first born son Jesus in sacrifice, fulfilling Abraham's failed call to duty. And today the fate of Israel rests in the hands of Christians eating the Sacrament like so many Gnomes gorging on a portly Cherub. |

DesiderataIn the twentieth century, Molech has served as a popular metaphor in the arts. He features prominently in Allen Ginsberg's Howl and in Fritz Lang's Metropolis. Molech seems to have followed the Phoenicians like the plague, infecting the entire Mediterranean rim, striking Carthage, the isle of Crete, and Tyre with a particular fury. Today the Phoenicians are gone, though their ashes dust the topheth boneyards and their shadows flit about Semitic genes.

|